-

Faculty of Arts and HumanitiesDean's Office, Faculty of Arts and HumanitiesJakobi 2, r 116-121 51005 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa EST0Institute of History and ArchaeologyJakobi 2 51005 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa EST0Institute of Estonian and General LinguisticsJakobi 2, IV korrus 51005 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa EST0Institute of Philosophy and SemioticsJakobi 2, III korrus, ruumid 302-337 51005 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa EST0Institute of Cultural ResearchÜlikooli 16 51003 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa EST0Institute of Foreign Languages and CulturesLossi 3 51003 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa EST0School of Theology and Religious StudiesÜlikooli 18 50090 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa EST0Viljandi Culture AcademyPosti 1 71004 Viljandi linn, Viljandimaa EST0Professors emeriti, Faculty of Arts and Humanities0Associate Professors emeriti, Faculty of Arts and Humanities0Faculty of Social SciencesDean's Office, Faculty of Social SciencesLossi 36 51003 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa EST0Institute of EducationJakobi 5 51005 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa EST0Johan Skytte Institute of Political StudiesLossi 36, ruum 301 51003 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa EST0School of Economics and Business AdministrationNarva mnt 18 51009 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa EST0Institute of PsychologyNäituse 2 50409 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa EST0School of LawNäituse 20 - 324 50409 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa EST0Institute of Social StudiesLossi 36 51003 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa EST0Narva CollegeRaekoja plats 2 20307 Narva linn, Ida-Virumaa EST0Pärnu CollegeRingi 35 80012 Pärnu linn, Pärnu linn, Pärnumaa EST0Professors emeriti, Faculty of Social Sciences0Associate Professors emeriti, Faculty of Social Sciences0Faculty of MedicineDean's Office, Faculty of MedicineRavila 19 50411 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa ESTInstitute of Biomedicine and Translational MedicineBiomeedikum, Ravila 19 50411 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa ESTInstitute of PharmacyNooruse 1 50411 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa ESTInstitute of DentistryL. Puusepa 1a 50406 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa ESTInstitute of Clinical MedicineL. Puusepa 8 50406 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa ESTInstitute of Family Medicine and Public HealthRavila 19 50411 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa ESTInstitute of Sport Sciences and PhysiotherapyUjula 4 51008 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa ESTProfessors emeriti, Faculty of Medicine0Associate Professors emeriti, Faculty of Medicine0Faculty of Science and TechnologyDean's Office, Faculty of Science and TechnologyVanemuise 46 - 208 51003 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa ESTInstitute of Computer ScienceNarva mnt 18 51009 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa ESTInstitute of GenomicsRiia 23b/2 51010 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa ESTEstonian Marine Institute0Institute of PhysicsInstitute of ChemistryRavila 14a 50411 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa EST0Institute of Mathematics and StatisticsNarva mnt 18 51009 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa EST0Institute of Molecular and Cell BiologyRiia 23, 23b - 134 51010 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa ESTTartu ObservatoryObservatooriumi 1 61602 Tõravere alevik, Nõo vald, Tartumaa EST0Institute of TechnologyNooruse 1 50411 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa ESTInstitute of Ecology and Earth SciencesJ. Liivi tn 2 50409 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa ESTProfessors emeriti, Faculty of Science and Technology0Associate Professors emeriti, Faculty of Science and Technology0Institute of BioengineeringArea of Academic SecretaryHuman Resources OfficeUppsala 6, Lossi 36 51003 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa EST0Area of Head of FinanceFinance Office0Area of Director of AdministrationInformation Technology Office0Administrative OfficeÜlikooli 17 (III korrus) 51005 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa EST0Estates Office0Marketing and Communication OfficeÜlikooli 18, ruumid 102, 104, 209, 210 50090 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa EST0Area of Vice Rector for ResearchUniversity of Tartu LibraryW. Struve 1 50091 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa EST0Grant OfficeArea of Vice Rector for DevelopmentCentre for Entrepreneurship and InnovationNarva mnt 18 51009 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa EST0University of Tartu Natural History Museum and Botanical GardenVanemuise 46 51003 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa EST0International Cooperation and Protocol Office0University of Tartu MuseumLossi 25 51003 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa EST0Area of RectorRector's Strategy OfficeInternal Audit OfficeArea of Vice Rector for Academic AffairsOffice of Academic AffairsUniversity of Tartu Youth AcademyUppsala 10 51003 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa EST0Student Union OfficeÜlikooli 18b 51005 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa EST0Centre for Learning and Teaching

Ismet Suleimanov received the University of Tartu Asia Centre scholarship for his MA thesis on the genocide memory of the Crimean Tatars

We are pleased to announce that the University of Tartu Asia Centre scholarship in the Faculty of Social Sciences was awarded to Ismet Suleimanov for his MA thesis. Read about why he chose the topic and his own personal connection to it.

What was your main trigger whilst choosing this topic for your thesis on the genocide memory and collective tragedy of the Crimean Tatars?

First of all, I would like to thank my supervisor Alevtina Solovyeva that she brought up the idea to write a thesis about Crimean Tatars, arguing that there are not many works about the ethnic group in English language. In the process of discussion, she shared with me a Finnish project dedicated to collective memory of Finnish people. Eventually, rotating and fitting the concept on the Crimean Tatars, the topic has been eventually chosen. Moreover, growing up in Crimea and especially within the Crimean Tatar environment, you, in one way or another, encounter such a statement « we shouldn’t live the trauma», however, it is always easier to say than to start implementing it. This thesis in a way proves that the trauma is rather is the indelible part of one’s life than a merely historical event during the Stalinist’s regime.

What challenges did you face during your research, and how did you overcome them?

I guess, I have encountered the same challenge as every researcher of the Soviet atrocities - the difficulty of the old generation to talk about the tragic memory, being insisted by the fear which was the dominant aspect of every evil empire. Additionally, the current political situation also dictates its rules, for example, those respondents who were in Crimea during the interview, were concerned about confidentiality since, in their opinion, the memory of the deportation is still ostracised and can cause a potential danger to the person and his/her surroundings. To overcome these aspects, I was just patient. First, you explain what your topic is about, then who you are. Gain trust through these tools and then people were usually opening up, unveiling whatever their memory wants them to reveal.

Were there any surprising or unexpected discoveries in your research?

Undoubtedly… simply the stories shared by my respondents had many surprising moments and turns. On the one hand, you know the official history and facts, but oral history helps to zoom in at the life of an individual and have some parallel path. I would say that in many cases the findings were obvious to me just because I am from this community and we are in the same boat, but, of course, it doesn’t mean that it is the same for someone who is outside it. Moreover, the stories shaped my existing pictures of, for instance, the process of return to Crimea or the meaning of 18th of May as a commemoration day.

Considering the current situation in Crimea today then what are the three most important lessons from your thesis that we, as a society should be aware of?

The only thing I want people to be aware of that for many ethnic groups that suffered during the Soviet time, justice has not been restored and their rights and thriving are still suppressed by Russia.

What advice would you give to other students or researchers interested in this field?

Working with oral testimonies requires patience and empathy. Having these two features will be the key to exciting discoveries.

Thank you!

Interview with the author after his graduation ceremony in 2024

Questions: Evelyn Pihla

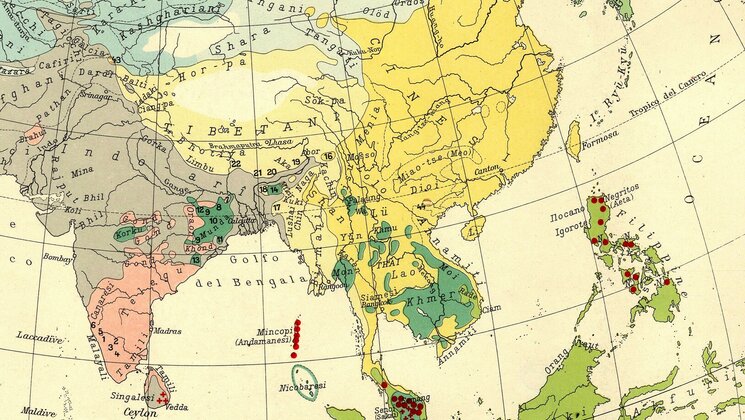

Southeast Asia's great power dilemma: a lecture and a discussion by Professor Joseph Chinyong Liow

Come to Blood Donor Day on 26 November!